Universities aren’t preparing their graduates for the workforce. We’ve learnt that students are seeking industry-relevant skills, and the industry definition and accreditation of higher education courses.

Universities aren’t preparing their graduates for the workforce. We’ve learnt that students are seeking industry-relevant skills, and the industry definition and accreditation of higher education courses.

Universities haven’t changed for a thousand years and offer very little flexibility to students. It’s a one-size-must-fit-all system. Students need flexibility in what they learn, how they learn, when they learn, how fast or slow they learn, and how much or how little they spend on learning.

Last week it was announced that Kim Carr has been given the higher education portfolio in the new Rudd government. Carr stated that his first task was to deal with the university sector’s funding cuts which are being used to implement the Gonski reforms to school funding. One way in which this may be achieved is to change the demand-driven system that has seen an extra 190,000 students pursuing undergraduate courses in Australia. Although Carr acknowledges that this has enabled more students from low socio-economic backgrounds to enrol in a degree, he is concerned about ensuring quality and excellence in the Australian higher education system.

Andrew Norton responded with a piece in The Conversation stating that a re-capping of the system will ration places on the basis of prior academic ability, and will disproportionately effect lower socio-economic groups. This outcome seems in contradiction to traditional labour party values of course, and the Gillard government’s goal of 40% of all 25 to 34 year olds having a Bachelor level or above qualification by 2025. But what is also problematic about Carr’s assertion is that the higher education system in Australia cannot expand in order to meet demand without compromising on quality.

The Australian government isn’t alone in facing this problem. In the UK, tuition fees have been increased substantially whilst teaching budgets have been cut, and government funding has been shifted to prioritising research. The US higher education system is also embroiled in debates about the rising cost of tuition fees and student debt levels reaching $1 trillion.

Martin Weller indicates in a recent article in The Conversation, that some of the current enthusiasm for MOOCs is a reaction to the crisis in higher education funding. People both within academia and outside of it (‘edupreneurs’ if you like) are trying to think of different ways of resolving this global problem. Audrey Watters and some other well known advocates of higher education, have recently convened a Bill of Rights and Principles for students to assert their needs and rights in a digital world. As she states, ‘We believe that online learning represents a powerful and potentially awe-inspiring opportunity to make new forms of learning available to all students worldwide, whether young or old, learning for credit, self-improvement, employment, or just pleasure. We believe that online courses can create “meaningful” as well as “massive” learning opportunities’. Online learning is certainly one way of scaling higher education if done properly.

Finally, back to the current state of higher education policy in Australia. What are Tony Abbott’s plans for the higher education system exactly? In all the leadership turmoil in the Labour party it’s been difficult to find out more about this, and the Liberal Party haven’t been very happy to oblige with further policy details. At his address to the Universities Australia conference in March he raised various points, including a focus on online learning as a way of both reducing the cost of provision, adding value and widening access for students. He also announced a new Coalition working group chaired by Alan Tudge. But that’s about all that we know so far.

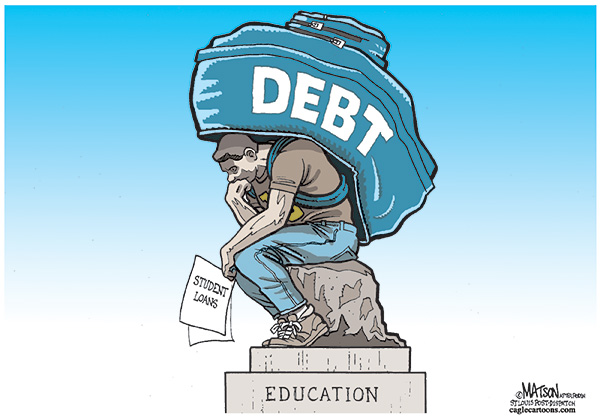

It’s been hard not to pick up the Wall Street Journal in recent months, and not see an article about the the spiralling cost of higher education to students in the US and the increase in defaults on student loans. Outstanding federal and private student-loan debt is approaching $1 trillion in the US. Student loans are now the second largest form of household debt, surpassing credit cards and car loans. The White House is now proposing to forgive billions of dollars in student debt over the next decade.

Although this sounds like a promising proposal for those riddled with education loan debts, it’s clear that many students have been encouraged to borrow too much money, with the expectation that such an investment will lead to longer term salary gains. In fact recent research by economics cautions that a university degree is no guarantee of promising employment. Unfortunately many students are being sold a false dream.

Many of those burdened with loan debts are mature students who are led to believe that by paying a great deal of money to attend a university that the benefits of a degree will ensure their economic success. These mature students are often working full-time and have family commitments so it’s not surprising that not all of them complete their degrees. This leaves them with mounting debts and no qualification to show for it. A report by the Harvard Graduate School of Education shows that just 56 percent of college students complete four-year degrees within six years. The US also finished last (46 percent) for the percentage of students who completed college once they commenced, of 18 countries tracked by the OECD.

So it comes as no surprise to learn that people are looking at alternative ways of gaining a higher education without getting saddled with long-term debt. Some of these initiatives are coming from young people such as Dale Stephens, a Thiel Fellow and proud high school drop out who founded UnCollege, which assists students with designing their own educational paths. MOOCs (Massively Open Online Courses) are also being used for self-directed learning. The challenge of certification for this form of learning still remains however. This is something that the team at Acavista are committed to finding solutions for.

There’s lots of discussion around MOOCs (Massively Open Online Courses) these days. A recent article in the Scientific American claims that there are a number of reasons why MOOCs have become so popular. The first is that brick and mortar campuses are unlikely to keep up with the demand for higher education. It is estimated that there is a need to construct more than four new 30,000-student universities per week to accommodate the children who will reach enrolment age by 2025. MOOCs are considered to expand the reach of existing campuses. There is also increasing demand from mature learners who enter higher education to further their education and career prospects. Another major factor is the sky rocketing cost of tuition fees and student debt, particularly in the US, where student loans are estimated to exceed US $1 trillion.

So, who is using MOOCs? Coursera, the largest of three companies offering MOOCs has 2.9 million registered users from more than 220 countries. Students from the US are the highest users, followed by India. The Guardian reported this week that early analysis of MOOC students studying at the University of Edinburgh has found that most of them are mature learners who already hold one or two degrees. This is in line with other analysis of MOOC data which shows that the primary use of MOOCs has been adults seeking professional development or lifelong learning. It’s also in line with our own initial research which suggests that adult learners are actively seeking new ways of learning and engaging in higher education.

It’s an exciting time to be in the higher education and ed tech space. The rules are literally being rewritten, as we speak. The US is very much at the forefront of these developments, and although Acavista is head-quartered in Australia, we’re certainly not prepared to sit on the sidelines and wait and see what happens.

The start of 2013 saw Barack Obama raising the issue of university accreditation in his State of the Union Address to Congress. In the Domestic Policy Blueprint that accompanied the speech he called for major changes to the nation’s system of accreditation. This development could provide a pathway for federal financial aid for competency-based learning, MOOCs and other innovations. He has called on Congress to either require existing accreditors to take value and quality into account, or to create a new alternative system of accreditation that would bypass the old gatekeepers.

The “credit hour” has been higher education’s gold standard. Not many people realise that the credit hour was devised by Andrew Carnegie in 1906 because he wanted to create a free pension plan for underpaid professors, enabling them to retire at a reasonable age. The “Carnegie Unit” was intended to be used to measure how much time students spent in each subject, as admissions to colleges were growing. It was never intended to be used to measure student learning, and there were concerns about it being misappropriated for this use shortly after it was introduced. All of this however, has remained unchanged, up until now.

In March 2013, the US Department of Education endorsed competency-based education, which some commentators have suggested could be a game changer for adult students, more so than the current hype around MOOCs. This signals a move away from the credit hour to measure student learning, to a focus on the achievement of competencies. It is suggested that competency-based education makes a degree more valuable since potential employers understand what students should be able to do (as spelled out in competencies) and the extent to which they can actually do it (their performance on assessments). In recent years, there has been a big expansion in universities offering competency-based offerings to working adults. For example, Western Governor’s University (WGU) has seen continued growth in it’s competency-based programs. Students at WGU on average complete their degree in 30 months with a total tuition of about US $17,000. This compares with the US $56,000 to state and student for four years at a public regional university in the US.

“Direct assessment” academic programs are regarded as the next step for competency-based assessment. This is because, unlike traditional academic programs, they are untethered from both course material and the credit hour standard (which links the awarding of academic credit to the hours of contact between academic staff and students).

According to Paul Fain, in the US the Lumina Foundation, the U.S Department of Education, State higher education agencies and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation are currently in negotiations about how this new model of “direct assessment” for academic programs might evolve further. Several institutions in the US are experimenting with online programs in direct assessment, with Southern New Hampshire University and Capella University being notable examples.

Acavista aims to be at the forefront of offering “direct assessment” programs, starting initially in the Australian market, but ultimately with global reach. For example, enabling students in developing countries who want to obtain a degree qualification to do so. Acavista is aiming to be the institution of choice for students wanting ultimate flexibility in their higher education experience. Like our tagline says, it’ll be the place where they come to “Choose a course. Get assessed. Get recognised!”